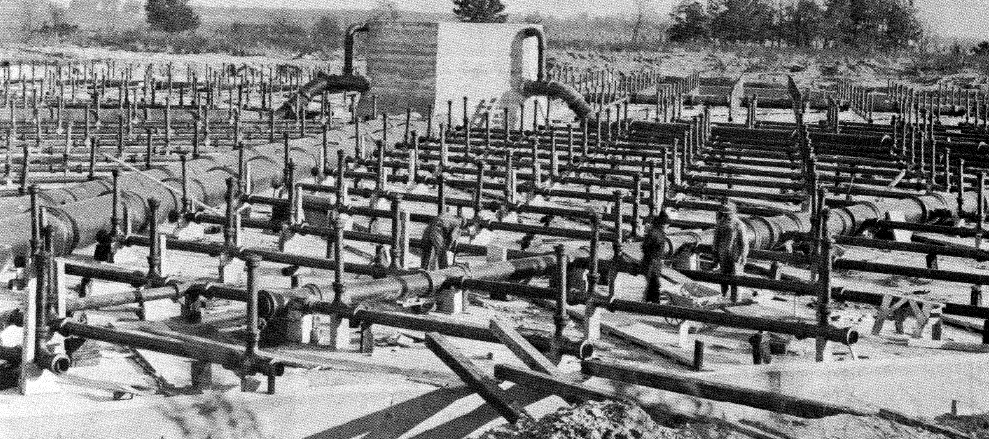

Above: Burke sewage plant “trickling filters” built around 1916. Photo from Wisconsin Historical Society

*******

One of Madison’s long-standing corporate powerhouses, Madison Gas & Electric (MGE), plans to build a new facility over one of the city’s worst toxic waste sites, the former Burke sewage treatment plant on Madison’s Northside.

This raises so many questions. Will MGE clean it up first? Or find out how far and wide the toxic wastes at the site–which were never fully remediated– have spread into groundwater, Starkweather Creek, and the community? Will DNR require MGE to do so?

Will DNR ask other entities that used the sewage plant since 1914 (the U.S. military, Oscar Mayer Corporation, the City of Madison, Dane County, Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District) for wastewater treatment and as a hazardous waste dump site to take responsibility for creating this toxic dump and cleaning it up?

Further, did MGE dump coal ash and other wastes at the site over the years? Is it, perhaps, buying the property in part to protect itself?

First, some context…

The former Burke plant has a long, convoluted–and toxic–history.

The plant was built by the City of Madison in 1914, and over the years was used by the City, the Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District, the U.S. Department of Defense, and Oscar Mayer. From the start, the plant treated Oscar Mayer’s growing amounts of animal processing wastes, and for a time Oscar Mayer operated the plant because its onsite sewage treatment plant couldn’t handle all its wastes. The Truax military base took over the plant for its own use during World War II.

Over its years of operation, a variety of hazardous and construction wastes, and animal parts, were also dumped near the plant, which is in a large wetland area south of the Truax Air National Guard base. The Truax landfill, currently owned by Dane County, is just to the north of the site. The Burke plant ceased operations in 1976, but was never fully remediated, nor was the landfill. A plethora of contaminants, including chlorinated solvents, several heavy metals, and most recently highly toxic PFAS, have been found there over the years.

After the sewage plant ended operations, a grocery store (formerly Copps, now Pick ‘N Save) and Shopko (now storage units) were eventually built over part of the site. Bridges Golf Course was created on fields around the site, partly over the old landfill, where sewage sludge and wastewater were spread for years. The land is also owned by the county.

Little to no remediation was done before these facilities were built; developers just built over the sludge, perhaps after removing the surface layers. A September 23, 1981 Cap Times article about the Shopko development cited a former alderperson hired by Shopko to promote the project: “‘Because of the expense of digging up a two-foot layer of ‘muck the consistency of chocolate pudding,’ he said, ‘few other commercial enterprises could afford to develop the land.'” This “chocolate pudding” was, of course, sewage sludge.

You can read a more detailed history here.

A lot has happened since we wrote this post in May 2019.

Starkweather Creek is heavily contaminated with PFAS

Starkweather creek flows just east of the Burke site, eventually discharging into Lake Monona a couple miles south. For decades, Burke wastewater flowed into a constructed ditch directly into the creek. This ditch, how called the “golf ditch” (because it flows through Bridges Golf Course), still drains the former Burke site (see maps here and here).

DNR data released in October 2019 and January 2020—from testing done as a result of years of MEJO advocacy—shows that Starkweather Creek water and fish have the highest PFAS levels in the state. Many low income subsistence anglers, largely people of color, fish in Starkweather Creek and Lake Monona. Lake Monona is also an extremely popular fishing destination for recreational anglers from all over the state.

In April 2020, MEJO released results from our own PFAS testing of Starkweather Creek sediments. We found the highest levels of PFOS, which builds up to high levels in fish, in the muck right where the golf ditch flows into the creek.

(Photo below: East Madison Community Center teens who participated in MEJO Starkweather PFAS testing on bridge near Burke golf ditch. This area is just west of the low income Truax apartments where these kids live. Read more about these teens and their work with MEJO here.)

Madison Gas & Electric purchased Burke site

In March 2019, Madison Gas & Electric, one of Madison’s most powerful corporate entities, purchased the Burke site for $5.5 million and plans to build an operations facility over the heavily contaminated soil, sludge, waste, and groundwater there.

On June 29, 2020 MGE’s consultants SCS Engineers, released a report, again finding significant levels of PFAS in groundwater at the Burke site. At two wells, the combined PFOS and PFOA levels range up to 41 ng/L, exceeding the Wisconsin Department of Health Services’ proposed groundwater standard of 20 ng/L for these two compounds. Total PFAS levels range up to 112 ng/L (ppt). If wider and deeper PFAS testing was done, much higher levels would very likely be found.

Numerous other contaminants have been found at the Burke site in previous testing—chlorinated compounds (PCE, TCE), fluorinated compounds, metals, petroleum compounds—but were not tested at all in recent investigations. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are highly likely to be there, but have never been tested. This 1989 report by a contractor for the Department of Defense scored the Truax Landfill, which overlaps with the Burke site to the north, high enough on the Hazard Ranking System (HRS) to be considered under Superfund.

A UW study done in 2005, and a nearly identical study done by consultants in 2016, found that the part of the creek where the “golf ditch” discharges is more toxic than any other area of the creek.

Will MGE investigate how far the PFAS and other contaminants traveled?

In their June 2020 report, MGE consultants concluded that “the elevated PFAS concentrations in groundwater associated with the buried sludge are not migrating off site” and therefore “active remediation to address the residual PFAS concentrations in the sludge is not necessary at this time.”

A limited number of groundwater wells were sampled and no testing was done in the sediments or water in the golf ditch to see what may have left the site over decades via this route, and what could still be leaching from it.

The DNR’s site investigation regulations, NR 716, say that responsible parties (MGE in this case) “shall conduct a field investigation as part of each site investigation required under this chapter, unless the department directs otherwise.

One key purpose of the field investigation, according to the rule, is to “Determine the nature, degree and extent, both areal and vertical, of the hazardous substances or environmental pollution in all affected media.” Also, the rule says that “Responsible parties shall extend the field investigation beyond the property boundaries of the source area as necessary to fully define the extent of the contamination.”

NR 716 rules also outline what should be included in a site investigation:

“(a) Potential pathways for migration of the contamination, including drainage improvements, utility corridors, bedrock and permeable material or soil along which vapors, free product or contaminated water may flow. (b) The impacts of the contamination upon receptors. (c) The known or potential impacts of the contamination on any of the resources listed in s. NR 716.07 (8) that were identified during the scoping process as having the potential to be affected by the contamination. (d) Surface and subsurface rock, soil and sediment characteristics, including physical, geochemical and biological properties that are likely to influence the type and rate of contaminant movement, or that are likely to affect the choice of a remedial action. (e) The extent of contamination in the source area, in soil and saturated materials, and in groundwater.” (emphasis added).

“Receptors” listed in (b) above mean waterways, wildlife–and presumably, people. “Resources” listed in (c) NR 716.07 (8) include: “Species, habitat or ecosystems sensitive to the contamination.”

It is scientifically inconceivable (and defies common sense) that the PFAS contamination at the former Burke site did not leave the site via the golf ditch and discharge into Starkweather Creek (as MGE’s consultants claim). The ditch was built purposely to drain the site. Shorter-chain PFAS compounds are very mobile in water. Longer-chain PFAS compounds, like PFOS, build up in sediments, where they remain for long periods of time and slowly release into the water.

It is also scientifically incontrovertible that shallow groundwater in this wetland area recharges the creek as it travels through the site.

So, will DNR ask MGE to follow agency laws? Will DNR ask MGE to test contaminant migration pathways offsite—e.g., down the golf ditch into Starkweather Creek sediments and water, affecting “resources” such as wildlife and fish? Will DNR ask MGE to assess the vertical and horizontal extents of PFAS and other contaminants in groundwater at the site and beyond?

Will MGE ask the U.S. military, Oscar Mayer Corporation, the City of Madison, Dane County, Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District–as past owners and/or users of the site, to share responsibility for this toxic sludge mess and take responsibility for cleaning it up? Will DNR require it?

Or, will this critical and troubling clause in the rule—“unless the department directs otherwise”— kick in to protect these powerful entities, as it has for many other corporate and government polluters in Madison?

Time will tell.

Unfortunately, the track records at other sites (see here and here) and former Oscar Mayer Company to the southwest of the Burke mess (also responsible for a good portion of it) do not give us much confidence. It appears that the NR 700 rules are filled with loopholes and discretion. In some cases, they appear to be almost voluntary.

Making matters worse, city, county, and state agencies also rarely enforce local and state stormwater laws that could be used to identify toxic chemical discharges from industrial and development sites into Starkweather Creek and the Yahara Lakes–and to require responsible parties to stop them.

Finally, as for MGE purchasing the Burke toxic waste site, we again pose the same question we raised earlier: Did MGE dump coal ash and other wastes at the site over the years? Is it buying the property, in part, to protect itself?