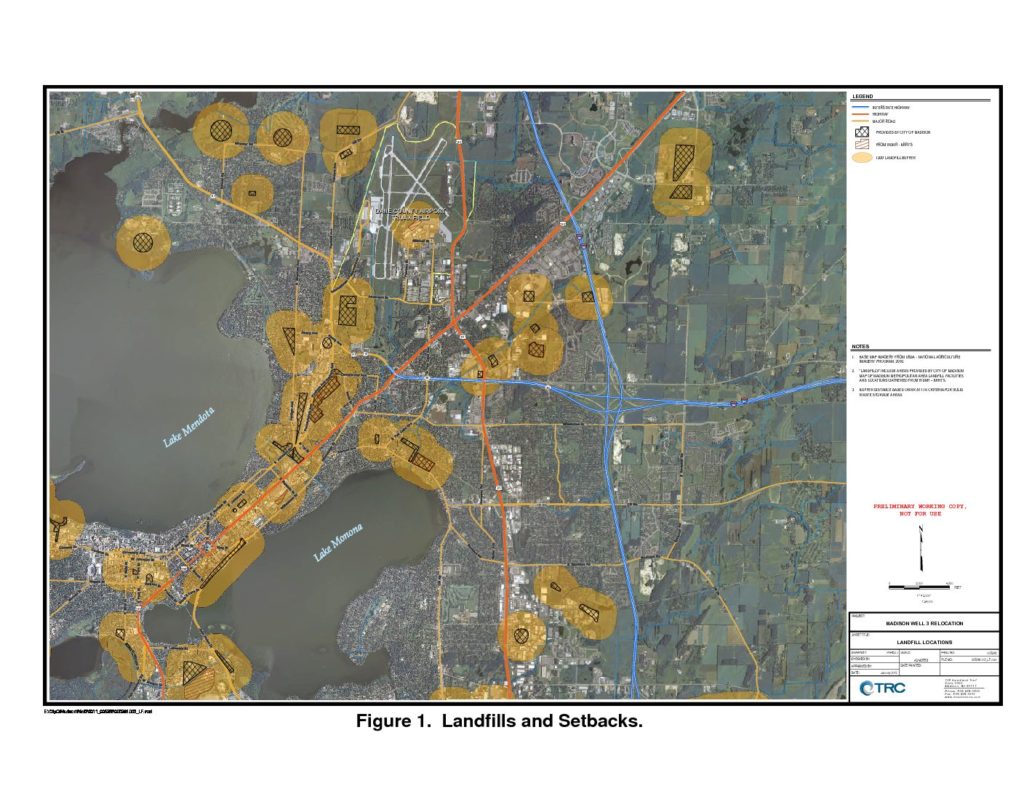

[Above: Madison north/eastside landfill map, compiled by TRC for the Eastside Water Supply Project in 2012 when the Water Utility was trying to find a location for a new well on the north or eastside after Well 3 was shut down and the city was growing dramatically]

This piece is a continuation of Parts II and III—see here and here. It will likely be changed/edited in the next few days. Some citations are removed; if you are interested in sources, please contact me: mariapowell@mejo.us.

******

In 2006 and 2007, reporter Ron Seely wrote a series of articles for the Wisconsin State Journal about Madison’s contaminated municipal wells and community organizing to do something about them.

At the time, manganese was the drinking water contaminant that prompted the most public outrage. People were also angry with the Madison Water Utility for lack of public transparency about the increasing contamination of city wells. Many lost trust in the agency.

Contaminants known to be more toxic than manganese—such as the carcinogenic chlorinated solvents PCE (perchloroethylene or tetrachloroethylene) and TCE (trichloroethylene)—had been found in Madison’s wells in prior decades (see Part I). But these compounds are not visible, so few people knew they were there. High levels of manganese turn water black, and many people in some parts of Madison had obviously discolored water. Complaints flooded into the Water Utility.

Where did the manganese in Madison’s deep wells come from? Water Utility and other government officials repeatedly told Seely that it came from “natural sources.” Seely, in turn, repeated this many times in his articles in 2006 and 2007.

Manganese is a natural element found in soils and rocks. Certainly some of the manganese in our wells comes from these sources. But is that the whole story?

“Unnatural” sources of manganese

On March 21, 2007, Seely reported that consultants hired by the city to investigate manganese sources to city wells found “high levels of manganese in the sandstone aquifer” from which Well 29 pumps water and “conditions that lead to the manganese dissolving in water are likely to remain.”

The article did not clarify the “conditions” that were “likely to remain,” though Seely noted that “[i]ronically, according to the engineers, a decision by Madison Water Utility engineers to blast the well to improve volume may have increased flow of sand and added to the manganese problem.” The engineers, who dubbed it the “well from hell,” recommended that a filter was the best way to deal with the problem. So a $2.5 million filter was put on the well, and it is still in use today.

Yup. The harder wells are pumped and blasted, the more manganese from the sandstone aquifer is likely to be in the water pumped up. Madison desperately needed this well to have sufficient water to serve increasing numbers of people in a growing city, especially with Well 3 shut down due to carbon tetrachloride, iron, and manganese contamination.

Manganese and iron also interact with chlorine added to the drinking water to kill viruses, bacteria, and other microbes, causing these metals to precipitate (settle out) in the pipes. So the more virus and bacteria problems increase, and the more chlorine is added to deal with them, the worse this problem can get.

So the manganese may be in part from “natural sources,” but the reasons problematic levels are in our drinking water (instead of remaining in the sandstone hundreds of feet down) are often not natural.

There are many other “non-natural” sources of manganese.[1] City and county engineers were well aware of one very obvious one–dumps and landfills–but rarely (if ever) mentioned these sources publicly. Why? Likely because the city and county are legally and financially responsible for them.

Madison: “It was a dump” (on a marsh)

Manganese and iron are commonly found in landfill leachates, “at concentrations that may be an order of magnitude (or more) greater than concentrations present in natural groundwater systems,” and it’s well documented that they can–and do– leach into groundwater. The “Science & Issues Water Encyclopedia” says:

“A release of leachate to the groundwater may present several risks to human health and the environment. The release of hazardous and nonhazardous components of leachate may render an aquifer unusable for drinking-water purposes and other uses. Leachate impacts to groundwater may also present a danger to the environment and to aquatic species if the leachate-contaminated groundwater plume discharges to wetlands or streams. Once leachate is formed and is released to the groundwater environment, it will migrate downward through the unsaturated zone until it eventually reaches the saturated zone . Leachate then will follow the hydraulic gradient of the groundwater system.” (see link for citations)

Oddly, through April 2007, Seely’s articles didn’t mention the potential that at least some of the manganese in Well 29 and many Madison wells may have come from the old dumps and landfills all over the city (see also here).

But about a month after the article about Well 29’s filter was published—and just two days after Seely reported that Well 3, deemed the “wicked witch” by the Water Utility, would be abandoned—Seely published a big expose: “Madison Underground: Contamination Central.”

The collection of articles included a nearly full-page graphic titled “Madison’s Garbage: A buried Legacy” along with a map that showed the location of all of the city’s landfills and many of the “historic dumps.”[2]

The caption at the top of the article, next to a photo of Demetral Landfill in the Eken Park neighborhood on the city’s northside, was: “Buried hazardous materials from factories of bygone years are haunting Madison and causing problems for the sinking of drinking wells, especially on the Isthmus.”

Under the notable headline “It was a dump,” Seely wrote: “Many cities are dealing with underground contamination, but in Madison the problems left us by old landfills have been magnified because of the city’s geography.”

Indeed, while cities everywhere have problems with leaching landfills, relatively few have Madison’s unique geography—large areas of marshes and wetlands surrounding several lakes, with a deep artesian aquifer beneath the city that provides all of its drinking water.

From the city’s beginnings, Madison’s leaders encouraged development on wetlands and marshes, and created parks along the lakeshore on filled land extending out into the lake. Residents, businesses, and industries, along with government agencies and the university, dumped wastes in the city’s marshy areas (especially on the east side and Isthmus) to help fill them in before development.

In addition to many open public dumping and burning areas, Madison eventually designated several sites as official city landfills that took industrial and construction wastes, along with residential, city, university, and military wastes.

Monona Terrace, Seely noted, was built on top of an old city landfill beneath Law Park on Lake Monona in the heart of Madison’s downtown (as we described here)

What was in city fill, dumps and landfills? As Seely explained in “Madison Underground,” “[m]uch of the Isthmus was once low-lying marsh and it has been filled in piecemeal over the years with everything from foundry sand to coal ash and cinders to trash. In more recent years the trash has included plastics, solvents, and other modern-day compounds that break down into cancer-causing chemicals.” Old newspapers also filled many dumps (see here).

Coal ash is well-known to be contaminated with iron and manganese (and many other toxic chemicals and metals).

Sadly, it seems that early Madison decisionmakers and leaders were oblivious to the long-term consequences of their wetland filling and landfill decisions–even with a major research university here with high-level scientists at their finger tips to advise them. The locations of these landfills were very ill-advised in a marshy city that gets its drinking water from aquifers beneath it.

Also, as I wrote in Part I, city officials believed that Madison’s wells were too deep to be affected by contamination at the surface.

They were wrong.

In the 1990s and 2000s, local media reported that landfills (among other kinds of surface contamination) were likely leaching contaminants downward and threatening drinking water, forcing city and Water Utility officials to publicly acknowledge this huge problem. But in recent years, city officials ignore this issue—or publicly pretend it no longer exists.

Old but forgotten news

Seely’s 2007 landfill expose wasn’t entirely novel news to Madison.

As outlined in Part II, Dan Allegretti of the Capital Times wrote in 1990 that Dane County has “more active landfills than any other Wisconsin county and nearly as many abandoned dumps as Milwaukee County. Many of these dumps are slowly leaking cancer-causing chemicals into the sandstone and limestone aquifers from which the Madison Water Utility draws some 31 million gallons of water each day.”

A DNR official told Allegretti at the time that Dane County led the state in the number of leaking landfills—and some had recently been placed on the EPA’s Superfund list.

One of the pieces in Allegretti’s collection, “8 of city’s once pure wells now tainted by chemicals,” explored the potential sources of the volatile organic chemicals (VOCs, such as PCE and TCE) that had been showing up in some Madison’s wells by that time.

“VOCs are among the most insidious of chemicals,” he wrote. “Including a large number of chemicals found in paint, solvents, industrial cleaning agents and gasoline, they are all but impossible to contain in a landfill. They pass right through clay liners and can escape even modern, properly constructed landfills to reach ground water.” (highlights added)

Given this, “some of the dozens of landfills and abandoned dumps located in and around Madison” were “prime suspects” for the VOCs being found in Madison’s wells.

What about iron and manganese?

As I wrote above, both manganese and iron are known contaminants of landfill leachates and are typically found at levels far over background.[3] Manganese often co-occurs with iron.

By the time Seely’s Madison Underground was published—and as Seely had already outlined in his April 30, 2006 article—nearly all of Madison wells tested in 2000-2005 had elevated manganese and/or iron levels. Manganese levels in wells 3 and 29 were deemed “high” during one or more of these years, and four wells—5, 7, 8, 29—had iron levels over the standards for one or more years. (Well 5, with the highest iron levels, was closed down in subsequent years, though it’s unclear why).

Seely’s table listed EPA’s advisory standards at the time: 0.3 ug/L (ppb) for iron and 300 ug/L (ppb) for manganese (they remain the same now). The manganese standard, Seely’s table noted, is based on “potential health risks-neurological problems” and the level that causes water discoloration is 50 ug/L (this is the “secondary standard, based on aesthetic concerns). The iron standard of 0.3 ug/L, also a secondary standard, “does not have health impacts, but can discolor water, affect taste, and stain water,” the table key said.

Well 7 (on N. Sherman Avenue) and Well 8 (in Olbrich Park), according to Seely’s 2006 article, had consistently high iron levels—well over the advisory standard for nearly all of the five years tested (Well 8 had a max iron level of 0.704 ppb and Well 7 of 0.446 ppb).

Many years later, iron and manganese are still elevated in several Madison wells, and three now have iron/manganese filters on them. Below are pre- and post-filtration iron and manganese data from a 2019 Madison Water Utility report:

Well 8 is not in the above table because, even though it has higher iron and manganese levels than any other Madison well, it has no filter. See further discussion below.

Is elevated iron only an “aesthetic” concern?

As discussed in Part III, the Water Utility assured the public that manganese is from natural sources and is only an aesthetic concern—even while a growing body of scientific research indicates that it can have neurological and other significant health impacts, especially for infants (see more articles here and here).

The key with Seely’s 2006 table admitted that manganese has “potential neurological effects,” but said iron “occurs naturally or can come from aging pipes” and “does not have health impacts.”

To this day, Madison Water Utility officials continue to refer to iron and manganese as only “nuisance contaminants”–see the Utility’s Water Quality report released on June 22, 2022.

This assurance is disingenuous for iron as well as manganese. It’s not clear how much was known in 2007, but more recent scientific studies show that though iron is an essential nutrient (and most people know that too little iron can cause health problems), excess iron can also have significant adverse health effects, especially in people with particular genetic disorders that lead to iron accumulation in the body.

For instance, this published study highlights “the importance of tissue iron accumulation in inflammation and infection, cancer, genetic, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases continuously increases.” Another study found connections between excess iron and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, infertility,and sexual dysfunction in men. A perusal of scientific literature shows that studies have found associations between too much iron in the blood and osteoarthritis, diabetes, heart problems, increased risk for certain bacterial infections, liver cirrhosis, long-term abdominal pain, testicular atrophy, severe fatigue, and skin coloring changes.

Are iron and manganese leaching into city wells from nearby landfills?

Though the table in Seely’s 2006 piece documented both iron and manganese problems in many Madison wells, oddly, the table in his Madison Underground piece a year later didn’t list iron as a landfill leachate contaminant—only manganese.

However, current and/or historical monitoring data from Madison landfills shows that, not surprisingly, significant levels of iron are also found in landfill leachates here.

Are these landfills contributing to iron and manganese in nearby wells? Below are a few examples of iron/manganese contaminated Madison wells near landfills that have highly elevated iron and manganese…

Truax Landfill and Well 7

Iron and manganese levels in groundwater monitoring wells under the Truax Landfill, very near Well 7, built in 1939, have consistently exceeded enforcement standards since monitoring began there many years ago, and they continue to be high. The DNR’s landfill database showed manganese levels there in 2021 of up to 500 ug/L and iron of up to a whopping 16,400 ug/L.

I’ve written extensively about the wide range of residential, industrial, city, university and military wastes that were dumped in the Truax Landfill. Madison city engineering’s 1984 report on Truax landfill stated clearly that its leachates were going toward Well 7, and supported this with groundwater diagrams based on data collected for many years prior. It predicted that the leachates could reach the well within 10-20 years. [4],[5]

Iron and manganese reached the well years ago, and a filter was installed in 2015 “to reduce the amount of these nuisance chemicals,” according to the Water Utility.

According to the Water Utility’s current report, “Water pumped from Well 7 contains a high level of iron and an intermediate level of manganese, minerals that can discolor the water. Unfiltered water, the report says, has around 0.46 mg/L (460 ug/L) iron and 31 ug/L manganese.

Utility officials never mention the possibility that this iron and manganese could be from the Truax Landfill. When we have asked about it over the years, they avoid the question.

Olbrich Landfill (and Kipp) and Well 8

As reported in an October 2021 WORT story, Water Utility water quality manager Joe Grande said Well 8 iron and manganese levels are the highest in the city and that this contamination “has been a longstanding issue.” Well 8 does not have a filter. (My family lived in apartments on the eastside from 1998 through 2005 and we experienced this discolored water many times.)

“The city regularly receives complaints about the water,” Grande told WORT, which is one reason the utility only uses the well seasonally. The utility needs to use this well when there are shortages, such as in the summer when the city’s water system is more strained. Since the closure of Well 15 in 2019 due to PFAS contamination, Grande said, the utility has to rely on this well more than in previous years.

Grande admitted that the Well 8 iron levels were two times the “Secondary Maximum Contaminant Level,” but emphasized that this standard was set for “aesthetic” concerns only (appearance, taste, or odor)—thereby dismissing any health concerns.

According to the Water Utility’s Well 8 report, in 2021 iron levels were 0.62 mg/L (620 ug/L) and manganese 52 ug/L. But the report downplays these levels and advises on how to deal with them as follows: “Water from Well 8 contains high levels of both iron and manganese, two minerals that can discolor the water. Water that contains iron or manganese above the EPA secondary standards, 0.3 mg/L and 50 μg/L, respectively, may stain laundry and plumbing fixtures. Instances of discolored water are random, infrequent, and temporary; the water usually clears up in 15-30 minutes without additional action. Running a lower level cold-water tap at full force for a few minutes can help to flush out the minerals that cause the discoloration. If the color persists, call the Water Utility’s Water Quality Line at (608) 266-4654. You should not use discolored water for drinking or cooking; instead run the water until it clears.”

The Water Utility, WORT reported, eventually plans to “overhaul” Well 8, which would likely include a manganese and iron filter, but not until 2025 at the earliest based on city budgeting.

Where is Well 8 iron and manganese contamination coming from?

Based on utility meeting discussions and internal communications, the Water Utility is aware that the Olbrich Landfill could be a source of iron, manganese–and chlorinated solvents–to Well 8. But (surprise, surprise!) utility officials never discuss this publicly.

Olbrich Landfill is several hundred feet or so from Well 8. It isn’t monitored anymore, but old monitoring data showed high iron and manganese levels in groundwater beneath the landfill (testing done in 1995 found 3,300 ug/L iron and 500 ug/L manganese; testing in 2001 found up to 1270 ug/L iron and 564 ug/L manganese. Significant levels of chlorinated solvents were also found in the 1995 testing: 18 ug/L of trans- 1, 2 dichloroethylene, 18 ug/L of cis-1, 2 dichloroethylene, and 5 ug/L of trichloroethyelene.

The key with Seely’s April 2007 table says Olbrich landfill was “a marsh that was mostly filled in with trash and with the dirt from basements of homes being built nearby.” It was operated from 1927 to 1930.

This is incorrect. David Benzschawel, a then recently-retired city engineer whose personal story was featured in Seely’s 2007 article series, shared a different description in his 1995 report about Olbrich landfill (from DNR files). He said the landfill, operated from 1933 through 1950, was “an open burn dump…the vast majority of the waste collected at this site was residential waste and demolition debris…A lot of the bottles and cans disposed of at this site are still evident in the waste cells. Steel cans have not yet completely rusted away. High iron levels in the groundwater analysis confirm the presence of large quantities of tin cans and metal scrap at this site.” (emphasis added).

A site investigation report done by Madison Kipp-Corporation consultants in 2012-2013 had a slightly different description. It said Olbrich landfill “accepted mostly residential and demolition waste including foundry sand, possible hazardous materials, and burned waste.”

Not surprisingly, the Madison-Kipp consultant report didn’t mention that Kipp-Corp itself sent wastes, likely including foundry sand and spent chlorinated solvents, to this landfill, which was very close to the factory. Foundry sand typically includes metals, including manganese and iron. Spent chlorinated solvents include PCE and TCE. (Kipp also sent industrial wastes to the Truax Landfill, as did several other local industries such as Ray-O-Vac.)

Former neighbors of the landfill remember Kipp and others dumping wastes there. The May 2021 50th Anniversary edition of the Eastmoreland Neighborhood Association included this recollection of a man who grew up next to the landfill: “Bob Narf remembers the Olbrich area by the ball diamonds on Atwood Avenue behind Hargrove used to be a city dump. “I, as a child, used to play there often. Madison Kipp Corporation, among others, dumped items there…”[6]

Iron and manganese could also be moving from groundwater beneath the Madison-Kipp factory to Well 8. Aluminum die-casting (what Kipp does) involves manganese and iron—so factory wastewaters and runoff likely also include these metals. Supporting this, very high levels of manganese and iron have been found in groundwater beneath Kipp in past monitoring. Some of the manganese came from the sodium permanganate purposely injected into the groundwater there in an attempt (failed) to treat PCE several years ago.

Though Madison Water Utility engineers are well aware of Olbrich and Kipp being potential sources of iron and/or manganese to Well 8, they never publicly mention them. [7]

Neighborhood activists have also been concerned about the huge plume of chlorinated solvents from Madison Kipp-Corp reaching Well 8; some of us think it probably did a long time ago (but passed the well and/or was diluted by lake water which is also drawn into the well).[8]

One key reason (rarely publicly stated, but explicit in internal communications) that the Water Utility hasn’t put a filter on Well 8 yet is that filters require wells to pump more water, and the utility is concerned that harder pumping of the well will draw Kipp’s VOC plume towards it more quickly.

The Water Utility recently installed a sentinel well about midway between the factory and the Well 8, to track how close the Kipp plume is to the well. The community advocated for a sentinel well for many years. To date the Water Utility hasn’t released any data from this well.

Sycamore Landfill and Well 29

Well 29–the “well from hell” described above–was sunk in 2002 very close to the Sycamore Landfill and, as described above, immediately had manganese problems. The manganese level Seely reported in Sycamore leachates in 2007 was 1,250 ug/L. He didn’t report iron levels.[9]

Seely’s “Madison Underground” table said the Sycamore landfill was “[t]he most problematic city site for industrial chemical contaminants” and was “used for disposal of city-collected large items such as appliances but also by commercial waste haulers, private firms and individuals.”

A quick perusal through the DNR’s landfill monitoring database for 2021 and 2022 shows that Sycamore continues to have elevated iron and manganese at many of its monitoring wells. Here’s a sampling of levels I noticed glancing through the data: iron up to 205, 699, 3560, 4460, 7490 ug/L (the last sample was from a “leachate manhole”) and manganese up to 468, 581, 693, 1140 ug/L.

Not surprisingly, manganese and iron are still problems at Well 29. The current Water Utility report for Well 29 says: “Water pumped from Well 29 contains elevated levels of both iron and manganese, minerals that can discolor the water” but the filtration system on the wells “reduce the concentrations of these nuisance chemicals.” See chart above for pre- and post-filtration levels.

But of course, as with other wells, the Water Utility never mentions the Sycamore landfill as a likely (or even possible) source of this iron and manganese.

Rodefeld Landfill and Well 31

Madison’s Well 31, less than ten years old (just drilled in 2014), already has “intermediate” levels of iron and manganese according to the Water Utility. It is not far west of the Dane County Rodefeld Landfill, and along the pathway of the surface ditches and creeks draining the southern part of the landfill (which discharge into Upper Mud Lake).

As with the Sycamore Landfill, a perusal through DNR database shows very elevated iron and manganese levels at Rodefeld Landfill in recent years and in the past. When Dane County applied to expand this landfill in 2013, it asked for exemptions due to exceedances of manganese levels at monitoring wells. The Environmental Assessment required for the expansion said: “Exemptions to groundwater quality standards in ch. NR 140, Wis. Adm. Code are requested for manganese at monitoring wells M-301A, M-302A, M-302B, and M-303A.” The county argued, using a very familiar trope, that “elevated concentrations of manganese…are not believed to be from the landfill or landfill related operations. Manganese is naturally occurring…”

What other contaminants are leaching from landfills into wells?

Answering this question would require another long article, if not a book. I’ll just provide a few brief points here.

All of the below contaminants are known to be elevated in leachates of municipal waste (but note that VOCs are excluded):

The text in the linked piece, reiterating what the table shows, says: “these constituents in leachate typically are found at concentrations that may be an order of magnitude (or more) greater than concentrations present in natural groundwater systems.” The table excludes “volatile organic compounds” (which would include PCE and TCE), but notes that “MSW leachate contains hazardous constituents, such as volatile organic compounds and heavy metals…”

As described in Parts I-III of this story, several experts and government officials believed that carcinogenic compounds such as PCE and TCE leaked from Madison landfills into drinking water wells.

Though it is no longer monitored, several chlorinated solvents were found in groundwater under Olbrich Landfill at levels at or exceeding standards in 1995 testing, including trichloroethylene (TCE) and two breakdown products of TCE and PCE—cis- and trans-1, 2 dichloroethylene. Cis 1, 2 dichloroethylene has been found in Well 8. This could be coming both from the Olbrich Landfill and Madison Kipp-Corporation, as I explained above.

PCE and TCE have also regularly exceeded standards at the Truax Landfill in ongoing monitoring. PCE has been showing up in Well 7 in recent years (and Well 15, which could also pull water from the Truax Landfill area, has had a PCE filter on it since 2013; it is now shut down due to PFAS levels). Levels of arsenic, cadmium, and nitrogen compounds exceeding standards have also been found at monitoring wells at Truax Landfill.

Excess sodium and chloride are also commonly found in landfill leachates. Seely’s April 22, 2007 Madison Underground table shows that chloride was leaching from many of the city’s monitored landfills at levels well over the state enforcement standard of 250 ppm (Demetral Landfill on Madison’s east side had a maximum level of 1,420 ppm).

Sodium and chloride are growing problems in several of Madison’s drinking water wells. Road salt is a key culprit, but leachates from landfills throughout the city are also very likely contributing. But, shhhh…..

PFAS

Last but not least, PFAS “forever chemicals” are almost 100% likely to be in city and county landfill leachates, but have not been monitored here (other than Refuse Hideaway west of Middleton, where they were detected).

PFAS compounds have been detected in nearly all Madison municipal wells, as I and local media have written about extensively since 2018.

Could some of the PFAS in our wells have come from city and county landfills? Why aren’t PFAS being monitored at closed and open landfills in Madison and Dane County? This topic would also require another long article to address. I will attempt to tackle these questions in a subsequent piece.

Were city landfills cleaned up? Are they still being monitored?

The caption with Ron Seely’s April 2007 Madison Underground map said “The city’s six licensed landfills have been closed and are still being cleaned up and monitored for contaminants.”

It’s unclear what the source of this statement was, but it isn’t true that all of the city’s six licensed landfills were “still being cleaned up” at that time (though they were and still are being monitored for some contaminants).[10]

As described in detail in MEJO’s “Madison’s Secret Superfund Site” series, the Truax Landfill was never cleaned up at all; it was simply capped and Bridges Golf Course was built over it. We have fewer details for the other licensed city landfills, but there is little evidence that they were still “being cleaned up” in 2007—if they ever were at all, beyond capping.

Olbrich was built without any liner and was never a licensed city landfill. When it was closed as a landfill (in the 1950s) it was capped with “granular fill” and “topsoil” (not clay) and developed into a park.

By 1995, “the city’s premier softball complex” had been built over the landfill, and the city wanted to improve the restroom and parking facilities. Benzchawel’s report summarizing investigations required by DNR before these improvements could go forward noted that “A small area of exposed waste was discovered along the ditch on the north side of the park.” The City, it noted, “is proposing to study this area in detail when the whole groundwater system below the landfill is studied in 1997 or 1998…as the Demetral, Sycamore and Olin Landfill remediations are nearing completion.”[11]

His report also said “depending upon the outcome of the more detailed groundwater studies, some kind of a landfill remediation along Starkweather Creek and this ditch might be scheduled between 1998 and 1999.”

There is no evidence that the “more detailed groundwater studies” at Olbrich Landfill proposed for 1997 or 1998 ever occurred. In 2001, the city got an exemption from DNR from doing some landfill investigations when the Olbrich Park Thai Pavilion was built, and in early 2005, city engineer Larry Nelson wrote the DNR requesting that “no further investigation and remediation be done” there. On March 7, 2005, the DNR approved this request.[12]

What’s happening now?

In the past, DNR, city officials, and the media openly discussed the impact of landfills on our drinking water quality, but the current approach is to avoid the topic altogether. While utility officials and city engineers may be discussing this internally, publicly it appears to be a verboten topic.

In the most recent Madison Water Utility report, for instance, landfills are mentioned only once as sources of contaminants to wells—as one of the possible sources for PFAS. In the source column for iron and manganese, it says “erosion of natural deposits.” (“Erosion of natural deposits,” according to this report, is the source of many if not most of the contaminants in our wells. Of course, as I wrote earlier, they do not mention that this “erosion” is occurring in part because of the heavy pumping of the wells reaching down into the bedrock in the deep aquifer—an unnatural process).

All of the above are known to be elevated in leachates of municipal waste.

The Water Quality report also shows that six Madison wells have PCE detects, but doesn’t list landfills as potential sources. (This doesn’t doesn’t include Well 15, which already has a PCE filter.)

Again, why won’t the Water Utility and other city officials discuss landfills as sources of contamination to its wells? Perhaps because they share legal and financial responsibilities for these landfills?

In the past, when landfill problems first came to light, public officials expressed concern about their public and environmental health implications. After city engineers and university researchers documented toxic leachates moving from the Truax Landfill towards Well 7 from the late 1960s through the 1980s, the city compiled a report about the situation in 1984. The report said “the City Health Department has an interest in the Truax Landfill because they are charged with protecting the environment of the City of Madison according to City Ordinance Sec. 7.46 and 7.47 which includes ground and surface water.”

But times have changed. Almost 40 years later, it seems that city and county officials have forgotten about—or just don’t care about?—their responsibilities to protect public and environmental health (City Ordinances 7.46 and 7.47 are still on the books). If they did, one of the first steps would be to openly admit that these historic and current dumps and landfills are still leaching a plethora of poisons into our drinking water. There is no easy answer to clean up these landfills or stop the leaching–but at the least we should monitor the leachates accurately and thoroughly to track leachate contaminant levels and their movements towards groundwater, surface waters, and drinking water wells over time.

Excerpt from the website above: “Monitoring wells at landfills allow scientists to determine whether contaminants in leachate are escaping into the local groundwater system. The wells are placed downgradient of the landfill at appropriate depths and at various intervals to intercept any contaminants and monitor their movement.”

If we don’t track the presence and movements of the contaminants leaching from our landfills, we can’t take steps to prevent or stop them and assure that people are not exposed.

Putting our heads in the sand about ill-informed past decisions—even if they were made by someone else—is not a responsible approach. It is unethical. It will just leave the poisons for our children and grandchildren to deal with–and to drink, knowingly or unknowingly.

Sadly, even here in highly educated, privileged Madison, it seems that ignorance is Bliss.**

**Miriam-Webster says the expression “ignorance is bliss” is “used to say that a person who does not know about a problem does not worry about it.”

*********

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Chlorine is sometimes added to water purposely to pull out the iron and/or manganese—e.g., https://www.jstor.org/stable/23349403 and https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40899-015-0017-4. While manganese and iron are often from natural sources such as soils and rocks, they are also commonly found in landfill leachates, “at concentrations that may be an order of magnitude (or more) greater than concentrations present in natural groundwater systems” (citation from link). According to EPA, manganese is also “commercially available in combination with other elements and minerals; used in steel production, fertilizer, batteries and fireworks; drinking water and wastewater treatment chemical.”

[2] Some of the information in this graphic was incorrect. See footnote 12.

[3] According to this website (MSW means “municipal solid waste”): “Leachate composition varies relative to the amount of precipitation and the quantity and type of wastes disposed. In addition to numerous hazardous constituents, leachate generally contains nonhazardous parameters that are also found in most groundwater systems (see above table). These constituents include dissolved metals (e.g., iron and manganese), salts (e.g., sodium and chloride), and an abundance of common anions and cations (e.g., bicarbonate and sulfate). However, these constituents in leachate typically are found at concentrations that may be an order of magnitude (or more) greater than concentrations present in natural groundwater systems. Leachate from MSW landfills typically has high values for total dissolved solids and chemical oxygen demand, and a slightly low to moderately low pH. MSW leachate contains hazardous constituents, such as volatile organic compounds and heavy metals . Wood-waste leachates typically are high in iron, manganese, and tannins and lignins. Leachate from ash landfills is likely to have elevated pH and to contain more salts and metals than other leachates.” (highlights added)

[4] Environmental consultants contracted by Dane County, owner of the Truax Landfill, have argued since monitoring began at this landfill that no plume is migrating from the landfill—even though extensive data from the late 1960s through the1980s show that a plume was migrating from it for a long time towards Well 7. They also claim, laughably, that the iron, manganese, VOCs, nitrates and other contaminants are not from the landfill: “There is no evidence that suggests a contaminant plume is migrating away from the landfill. Groundwater quality data exhibit both increasing and decreasing trends at wells both upgradient and downgradient of the landfill. At some well nests (e.g., MW-5A/5B), deeper wells show higher concentrations than their shallower neighbors. This is an indication that the impact is not from downward migration of contaminants from the near surface (i.e., the landfill). Constituents such as arsenic, iron, lead and manganese are often naturally elevated above drinking water standards in groundwater. Nitrate is also commonly found in groundwater in residential and agricultural areas due to infiltration of constituents found in most fertilizers.”

[5] Why didn’t these contaminants show up at Well 7 earlier, as predicted? It’s likely because other deep high capacity wells, including Well 15 and Oscar Mayer’s deep wells, were drawing groundwater away from the well. In fact, as I reported previously (see Part III), when the city realized in the 1980s that the Truax Landfill leachates were moving toward Well 7, it knew the Oscar Mayer wells protected the well by drawing the water in another direction—and later the city decided to purposely use Oscar Mayer wells as a de facto “pump and treat” for the plume.As I wrote: “A March 12, 1985 DNR memo with minutes from a meeting with the City of Madison about local landfills noted that Benzchawel said that “groundwater flows toward the Oscar Mayer wells to the southwest…” which pumped 4.5 million gallons a day at that time. Because Well 7 was only used in the summer and only pumped 1.5 million gallons per day, he opined that “there was little chance of contamination as long as Oscar Mayer is pumping its wells at such a great rate.” But after chlorinated solvents were detected in Oscar Mayer wells in the 1980s, the company began shutting some of its contaminated wells down and drawing municipal Well 7 water instead. By the mid-2000s, all of the Oscar Mayer wells were shut down due to contamination and the company’s water came entirely from Well 7. Now, with Oscar Mayer wells off and Well 7 pumping harder to make up for the loss of Well 15—and with thousands of new housing units planned in the neighborhood–will more iron, manganese, chlorinated solvents and PFAS show up at this well? The Well 7 report says: “Drilled in 1939, Well 7 has a pumping capacity of 2200 gallons per minute; however, the pump typically delivers 1750 gallons per minute through the use of a variable frequency drive…In 2021, Well 7 pumped 585 million gallons of water. The 5-year average is 534 million gallons pumped annually.” Using1750 gallons per minute, this comes to 2,520,000 gallons per day. How much more did it draw up during the years Oscar Mayer was also relying on it? How far has the Truax Landfill plume pulled in its direction since the 1980s?

[6] Mr. Narf’s other memories about the area are also interesting—and sad: “Across the river, the flower garden area was a swamp up to Sugar Avenue. A creek wound its way through there. We used to skate there in the winter. Tramps also used this area for camping. My brother invited one of them home for a Sunday meal once. Starkweather Creek was a fabulous fishing area. Under the railroad crossing we could see the Blue Gills as they came to bite our hooks. The edge of Lake Monona, at that time, came much closer to Atwood Avenue and the dredging through the years has made the park much larger, filling the lake. The Olbrich hill contained a ski jump, and a toboggan slide was added later. Hudson Park beach contained a swimmers’ pier about 150 feet long, a high dive out further, a 29-foot pier halfway out and a lifeguard stand out near the high dive. Needless to say, the water quality was much better, although ‘dog days’ in August, even then, made the lake dirty. Lake Monona was a fisherman’s paradise. I used to row a boat out about 300 yards from shore, directly off of the Eastside Businessmen’s Association building, and in no time have my limit of Blue Gills, Perch, etc. It took about half an hour to achieve that usually. In the early evening, a limit of Walleyes could easily be caught.”

[7] The city also went out of its way in the past to deny any groundwater impacts related to the Olbrich Landfill, while recognizing that its leachates went directly into the lake right next to the well. City engineer David Benzchawel’s 1995 report concluded that “the landfill is located on a peninsula so that groundwater flow will end up in the Lake no matter which way it runs.” But as far as Well 8, just a few hundred feet from the well, he wrote, that “as a precaution, the water quality at the well was reviewed and no problems were evident. There are no other groundwater users affected by this landfill.” “An environmental investigation of the site did not provide any evidence that the proposed facilities would have problems with landfill gas or groundwater pollution… (highlights in original).

[8] From WORT: “In 2013, a shallow monitoring well uncovered trace amounts of PCE in the upper aquifer about 600 feet from the well — although no PCE has ever been detected in Well 8 itself.”

[9] Also, tetrachloroethylene of 16 ppb and trichloroethylene of 22 ppb (health standards for both are 5 ppb).

[10] The source was likely city engineers Dave Benzchawel and/or Larry Nelson, cited elsewhere in Seely’s article. Both men were intimately involved with decisions about remediating and closing the city’s landfills.)

[11] Interestingly, it also noted that “All wastes encountered during excavations for the subbase and utilities will be disposed of at the Dane County Rodefeld landfill.”

[12] There were also some strange inconsistencies in information in Seely’s Madison Underground landfill map/table about where old dumping areas were located. For instance, “Dr. West’s Hog Farm,” a “piggery farm” where the city sent garbage to be eaten by hogs from the sometime shortly after 1914 through the mid-1940s, was located just southwest of the Truax Landfill next to the Burke sewage plant. The table says Dr. West’s Hog Farm, where the “[c]ity arranged to haul garbage where food wastes were eaten by the pigs,” was located at Wheeler Rd from 1945 to 1953, but doesn’t mention the earlier location next to the Burke plant. Apparently the piggery moved to the Wheeler Road location after the military took over much of Truax Field and Burke plant during the war. (According to the table, the Cherokee condominiums and golf course were eventually built over the area where the piggery farm was.) The incorrect and/or inconsistent information likely came from city staff David Benzchawel, who had retired just a week before the story was published. A caption with the map said: “For more than 20 years David Benzchawel, a civil engineer for the city checked such sites and located them on a map so they can be properly managed and monitored.” It also included a disclaimer, “This map is not a complete listing of all abandoned or closed landfills.”