In 1970, just before Madison’s first Earth Day, Oscar Mayer installed a mile-long system that misted artificial chemical perfumes around its sludge lagoons–after decades of neighborhood complaints about the sewage stench.

What a unique and creative corporate greenwashing approach! Read more below.

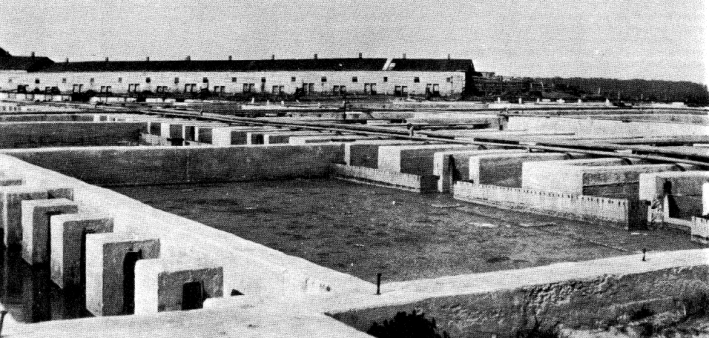

(Above: wastewater filtration facilities at Madison’s Burke sewage treatment plant, used by Oscar Mayer from 1950-1978).

Oscar Mayer’s Earth Day, 1970: Spray chemical perfumes on sewage stench!

As we described in detail here, Oscar Mayer & Company, the meatpacking company that located on Madison’s north side in 1919, did much more than slaughter animals and make meat products. The factory included research laboratories that created pharmaceuticals, pesticides, chemicals for sewage treatment, and likely myriad other chemical compounds used in its operations and food processing.

The factory site eventually became a little city into itself. It manufactured plastic wrap and packaging for its products. It had its own sewage treatment plant, produced its own power (burning coal and natural gas), and sank several water wells to draw from the deep artesian aquifer under the city to use for its ice business and pump into its hotdogs (until somebody discovered in the 1980s and 1990s that the wells were too contaminated with chlorinated solvents to use anymore, after which it used water from public municipal wells).

Burdgeoning sewage wastes created a horrific stink in the neighborhood–and discharged into waterways

Oscar Mayer grew rapidly and in time became the city’s top private employer. Animal slaughtering and factory processes generated gigantic quantities of animal and sewage wastes. After World War II, the company took over the city’s defunct sewage plant at Burke just to the northeast, which had been used by the military during the war. This inadequate plant couldn’t handle all of Oscar Mayer’s wastes and—one way or another—they spewed into Starkweather Creek, the Yahara River, and all the lakes. Excess Oscar Mayer sewage was spread on the land and community gardens around the Burke sewage treatment plant, just north of the Eken Park neighborhood, east of the Sherman neighborhood, and west of the Carpenter Ridgeway neighborhood. Nearby residents repeatedly complained of stench, but half-hearted efforts to quell it never worked very well.

In the ‘50s and 60s, Oscar Mayer did insecticide experiments at the Burke site, which leached DDT and other toxic insecticides into Starkweather Creek.

The City of Madison was anxious not to drive away its top employer and bent over backwards to assure that Oscar Mayer’s financial success and many expansions wouldn’t be impeded. This meant not doing much (or anything) to slow or stop the pollution spewing from the factory—and in some cases, facilitating it. Starkweather Creek became such a foul ditch that at one point an alder proposed treating it like a storm sewer and covering it up with cement. Another suggested flushing it out with Oscar Mayer cooling water.

Environmental regulations developed in the 1970s–at federal, state and local levels

In the 1960s, following Rachel Carson’s seminal book “Silent Spring,” environmental regulations and public concern about pollution increased. In the 1970s, the creation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) led to several major regulations, including the Clean Water Act, which aimed to create “fishable and swimmable” waters by 1983 and to “eliminate all discharges of pollutants to navigable waters by 1985.”

EPA charged states with administering these laws, which led to the Wisconsin DNR’s Wisconsin Pollution Discharge Elimination System (WPDES)—the state version of the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) created per the Clean Water Act to meet its goals. One state policy goal was “that the discharge of toxic pollutants in toxic amounts be prohibited.”

The City of Madison also developed local water quality regulations following the adoption of the Clean Water Act. On June 4, 1975, a public notice of Madison General Ordinance (MGO) 7.46 (Water Pollution Control) appeared in the Wisconsin State Journal. “This Ordinance is designed to prevent polluting or spilled material from reaching lakes or streams where it can create a hazard to health, a nuisance or produce ecological damage and to assess responsibility and costs of clean up to the responsible party.” “It shall be unlawful for any person, firm or corporation to release, discharge, or permit the escape of domestic sewage, industrial wastes or any potential polluting substances into the waters of Lakes Mendota, Monona, Wingra or any part of Lake Waubesa adjacent to the boundaries of the City of Madison, or into any stream within the jurisdiction of the City of Madison, or into any street, sewer, ditch or drainage way leading into any lake or stream, or to permit the same to be so discharged to the ground surface.”

Potentially polluting substances included, but were “not limited to” fuel oil, gasoline, solvents, industrial liquids or fluids, milk, grease trap and septic tank wastes, sewage sludge, sanitary sewer wastes, storm sewer catch-basin wastes, oil or petroleum wastes. Responsible parties who discharged such spill material, the ordinance said, “shall immediately clean up any such spilled material to prevent its becoming a hazard to health or safety or directly or indirectly causing the pollution to the lakes and streams under the jurisdiction of the City of Madison.”

Spills were to be immediately reported to the Madison Police Department, which would direct the report to the proper agency, and the responsible party (or parties) would be held financially responsible for the cost of cleanup. Enforcement was up to the Director of Public Health (or his/her designee) and the penalty could be up to $500 a day for failure to comply, with each day of violation a separate offense.

(Madison General Ordinance 7.46 still exists–though a few specifics were changed in 1998. Spills are no longer to be reported to MPD, and the fines are up to $50-$2000 per day. Has Madison ever used this ordinance to fine a local industrial polluter? See later installments to this story).

Nothing else worked, so Oscar Mayer sprayed chemical perfume on the stench!

Unfortunately, the horrific sewage stench in the neighborhood—not addressed by any of the new environmental laws–continued. In 1970, when the first Earth Day was organized in Madison, the stench in the neighborhoods around the Burke plant was so bad that the company, asked by government authorities to do something, installed a mile-long system that misted chemical perfumes around the sludge lagoons and sludge spreading fields with different artificial spicy and flowery smells—including lilac, cinnamon, carnation, citrus mint–every day. Some older Truax neighborhood residents remember this—and they are not pleasant memories…

Did the chemical perfume misting work to cover up Oscar Mayer’s sewage stench? Did new environmental regulations created in the 1970s force Oscar Mayer to finally stop–and clean up–its pollution? Well, it’s a long story…

There’s a lot more to this story. Here’s the full blow-by-blow saga of what happened from 1960 to 1981 (Part II of Oscar Mayer polluted Starkweather Creek, Yahara River & Lake Monona for 100 years).