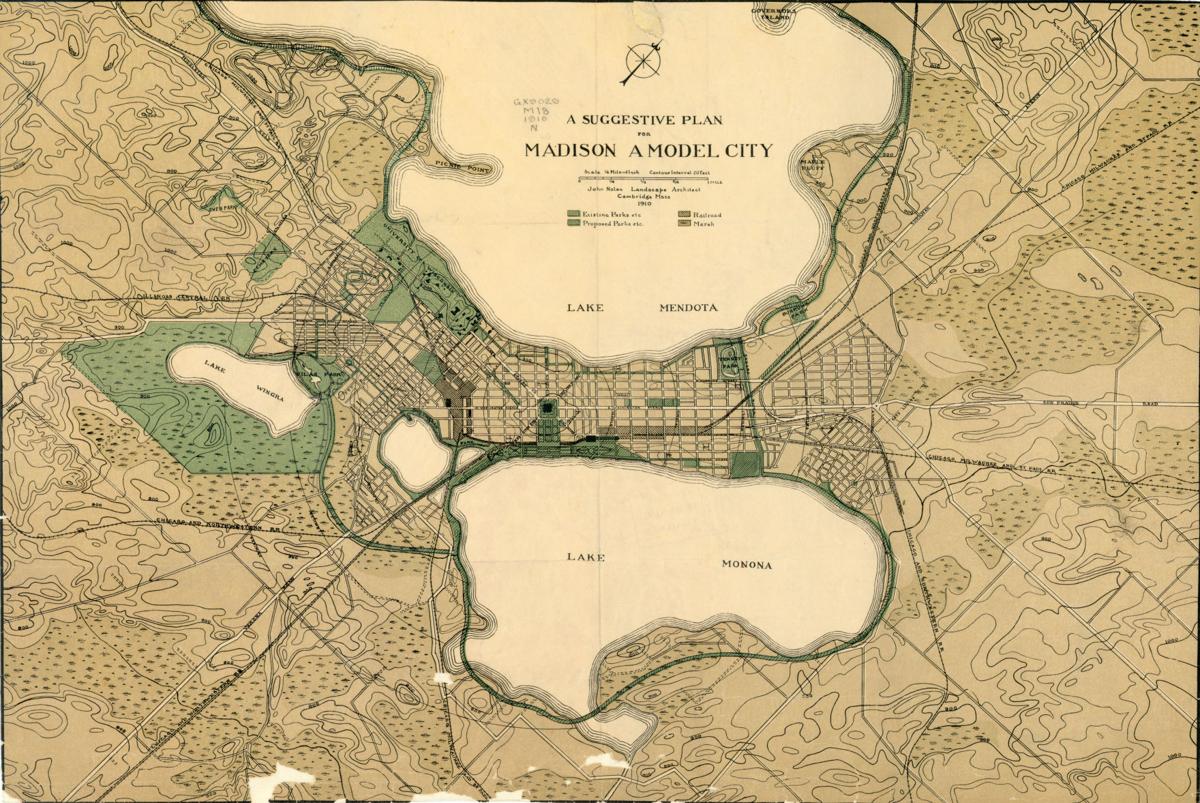

[Above: A plan by John Nolen from 1910 shows a vision for Madison as a model city. The plan shows existing and proposed parks, railroads, and marshes in a color coded key. (WHS #100762)

This is an excerpt from a longer piece. Other than links to local newspaper articles, the citations are removed. If you want sources for particular points, or have corrections/comments/questions, please contact Maria Powell at mariapowell@mejo.us

*****

As described in “Madison fouled its own nest, Part I” Madison polluted its pristine lakes—especially Lake Monona–with sewage within a few decades of the city’s founding. As the city grew rapidly, and its shallow residential wells also became contaminated, city leaders debated whether to get public drinking water from Lake Mendota or from drilled wells drawing from deep artesian aquifers beneath the city.

Eventually city leaders decided to sink many very deep wells, up to around 1000 feet deep, believing that contamination on the surface would not make it down that far.

But they were wrong. By the late 1960s and 1970s, researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey reported that the heavily-pumped deep municipal and industrial wells had reversed the hydrogeology in much of the Madison area—springs no longer fed the lakes, but instead the lakes were being drawn downward, along with contamination in them, into the groundwater.

In 1978, Daniel Allegretti reported in The Capital Times that “…in all likelihood, surface water is beginning to be drawn down into the underground water table.” The Water Utility manager told Allegretti that “cleaning up surface water—area lakes and streams—is ‘our first line of defense’ in protecting drinking water supplies…If the concentrations (of pollutants) are building in the lake water they could be in the groundwater in the next 10 years or so.”

By this time, the U.S. Geological Survey, the Madison Engineering Department, and Water Utility knew that municipal and industrial wells, especially on Madison’s north side under Truax Field, had already pulled contamination on the surface down into deep groundwater and some wells.

In 1983 another Capital Times article by David Blaska reported on the discovery of several carcinogenic volatile organic chemicals in two west side wells.

Allegretti wrote another collection of articles in 1990–“Water, water, everywhere…but is it safe to drink?” By then, eight of the city’s 24 wells had detectable levels of volatile organic chemicals and others were in danger of contamination.

Importantly, Allegretti noted, the pollution “may have been there for many years and gone undetected simply because the technology did not exist until the past decade to detect VOCs at the minute levels, in factions of parts per billions…”

Now, in 2022, all of Madison’s wells have detectable VOCs, PFAS, metals, and/or other contaminants. Several have expensive filters, paid for by ratepayers (us). Some if not most of these detections are due to improved testing technologies. How long did Madisonians drink these poisons without knowing it?

Dane County led the state in leaking landfills

Allegretti’s 1990 article honed in on city “fill” (garbage, debris, coal ash, and various other materials used to fill in Madison’s large wetland areas for urban development), as well as city landfills, as likely sources of the city’s increasing groundwater problems.

“No one is sure where the contamination is coming from” Allegretti wrote, but “it could be that some of the thousands of tons of fill used in the city decades ago was contaminated.” He pointed to the “dozens of landfills and abandoned dumps in and around Madison” as “prime suspects.”

Dane County, he reported, has “more active landfills than any other Wisconsin county and nearly as many abandoned dumps as Milwaukee County. Many of these dumps are slowly leaking cancer-causing chemicals into the sandstone and limestone aquifers from which the Madison Water Utility draws some 31 million gallons of water each day.”

VOCs found in paint, solvents, industrial cleaning agents and gasoline “are all but impossible to contain in a landfill,” he explained. “They pass right through clay liners and can escape even modern, properly constructed landfills to reach ground water.”

Notably, a DNR official said that at that time, Dane County led the state in the number of leaking landfills—and some had recently been placed on the EPA’s Superfund list.

“People are finally realizing that the whole system is interrelated…”

Allegretti’s piece deemed abandoned dumps that have not yet been investigated or discovered yet “of equal concern” as known landfills, because “an old dump can contaminate Madison’s drinking water even if no well is located nearby.” Further, he explained, “Madison’s deep, high-capacity wells draw in water for miles around, making it nearly impossible to identify the source of a particular contaminant.” This means that city wells can draw in agricultural chemicals “as well as water from Madison area lakes, which are barely suitable these days for swimming much less drinking.”

In the Madison area at that time, the water table was 20 feet lower—and closer to the wells, 80 feet lower—than it was before the deep wells began pumping, in an area 20 miles across (stretching from Sun Prairie in the northeast to beyond Verona in the southwest). “As the city’s population grows and the demand for water increase,” Allegretti wrote, “so will the area affected by this dramatic drawdown of the water table.” This also draws groundwater away from rivers, creeks, and lakes, and dries up springs.

Echoing his 1978 article, he reminded readers that the city’s “powerful” wells pull water from the lakes into the ground water and toward the wells–and some scientists believe this could be a source of some drinking water contaminants. He brought up the chlorides in city wells, discovered about ten years after the detection of chlorides in the lakes in 1970.

Concluding the article, Ken Bradbury, a geologist from the Wisconsin Geologic and Natural History Survey, was aptly cited. “People are finally realizing that the whole system is interrelated…”

Sadly, just three years after this article was published, Allegretti died of cancer at age 45.

“Ancient pre-glacial river valley” runs through Truax Field

Allegretti’s 1990 article briefly mentioned “the Truax site where for years the U.S. government dumped waste from munitions” and said the landfill “poses a threat to two Madison city wells.”

Indeed, as documented in Madison’s Secret Superfund Site (see Part II), throughout the 1970s and 1980s the city had been quietly documenting a plume leaching from the former Burke sewage treatment plant and Truax landfill. After the city engineering department issued a report in 1984 mapping these plumes, the city and county argued for years about who was responsible for the landfill.

In 1990, the DNR finally issued the first of a series of consent orders to both entities requiring them to investigate the landfill and clean it up. Environmental consultants contracted by the city/county eventually advised “passive remediation” (doing nothing) and capping for the landfill. So no remediation was done and it was capped with clay from near Reindahl Park area. In 2000 the Bridges Golf Course was built over it.

A fascinating hydrogeological reality that came to light during the landfill investigations was the “ancient pre-glacial river valley” under the Truax Field area. Geologists had known about this since the late 1960s and early 1970s, if not earlier. A 1983 Dane County Regional Planning Commission report on Starkweather Creek noted: “The West Branch of Starkweather Creek is largely underlain by the pre-glacial Yahara River Valley. The bottom of this buried valley is about 260 feet below the land surface in the vicinity of the old Burke Wastewater treatment plant. For a distance of approximately four miles above Milwaukee Street, the bedrock surface underlying the West Branch is 250-300 feet deep, with a corresponding thickness of glacial drift…”

This pre-glacial valley affects the horizontal and vertical groundwater flows in the area and how deep well pumping influences them. According to the DCRCP report, “the upper aquifer is generally leaky” in the Madison area, so water from the surface can leach down into the lower aquifer. Because of the deep pre-glacial valley underlying it, the upper aquifer under the West Branch of Starkweather is “more leaky” than under the East Branch, so “it is more sensitive to deep pumpage.” This deep pumpage, in turn, draws contamination from the surface down deep into the aquifer.

This 1988 Preliminary Assessment of Truax Field by the Air National Guard shows a diagram of the pre-glacial river valley. (The January 2022 Air National Guard site investigation has more updated maps) and the DNR’s comments on this document explicitly call it out (see footnote).[1]

Environmental consultants working on the Truax Landfill site in the 1990s, drawing from the earlier city and USGS reports, knew this ancient river valley affected the flow of groundwater (and contamination in it) in key ways, though not well understood. In March 1993, the consultant contracted by the Truax Landfill PRPs told DNR he believed that “there is funny groundwater flow south of Oscar Mayer as well as west of Truax probably related to the bedrock valley buried below the surface.”

Wisconsin State Journal: Madison Water Utility “closed mouthed” about problems

Sixteen years after Allegretti’s story, Wisconsin State Journal reporter Ron Seely did a four-part series about the challenges facing Madison Water Utility in regards to its aging infrastructure and contaminated wells.

The first part of Seely’s 2006 series was titled “An Aging System” and subtitled “And officials have been less than forthcoming with the public.” “Students at East High School,” it began “were among the roughly 9,000 people who, for a short time at least, were drinking city water contaminated with high levels of an industrial pollutant that can cause liver, kidney or lung damage.” The contaminated water came from Madison’s Well No. 3, drilled in 1928.[2],[3]

The State Journal’s three-month investigation into the Water Utility’s management of drinking water in previous years, Seely reported, “revealed dubious management practices that may lessen trust in both the utility and the safety of drinking water, an aging system that can allow more pollutants in, and above all, the utility’s reluctance to be forthcoming about the water we’re drinking.”

The Water Utility, according to Seely, had been “closed mouthed” about several drinking water problems from 2000-2005. Among other things, the utility failed to keep adequate records of citizens’ complaints to the Public Service Commission (most about water discolored by manganese).[4] It also incorrectly reported carbon tetrachloride levels of 2.9 parts per billion to the public, instead of 8.3 parts per billion, found in one test in October 2000 (the standard at the time was 5 ppb). The State Journal’s investigations discovered this discrepancy in utility records. Water Utility officials said the lower number was a typo.

Tom Stunkard, drinking water specialist with DNR, said the high reading wasn’t a violation of standards, because it was a one-time finding and a second test came back at levels below the EPA limit. It didn’t mean the well must be shut down. Any harmful exposure to the chemical, he opined, was “unlikely,” but the incident eroded public confidence. “It makes you start to wonder what else might be wrong,” he told Seely.

Contaminants in nearly all Madison wells–where were they from?

The State Journal’s investigations revealed that in addition to the carbon tetrachloride in Well 3, several other contaminants had also been detected in numerous Madison wells. A nearly full-page graphic included data on manganese, iron, tetrachloroethylene and trichloroethylene for all Madison wells from 2000-2005.

A companion article by Seely also raised concerns about viruses showing up in Madison’s wells. “Viruses aren’t supposed to be able to penetrate an aquifer as deep and naturally protected as Madison’s,” Seely wrote. (It’s a peculiar statement, given the focus of the article series. If toxic contaminants from the surface make it into the deep wells, it isn’t surprising that viruses do too.)

DNR’s Stunkard praised the utility, but raised concerns about “suspicious levels” of volatile organic compounds in some wells. Carbon tetrachloride was only detected at Well 3, but tetrachloroethylene was detected at seven wells during 2000-2005, approaching health standard of 5 ppb at two of them (Well 9 and 15). Trichloroethylene was detected at six wells, though below the standard of 5 ppb.

All the wells had some level of manganese, though only Well 3 and 29 had levels (some years) approaching the EPA’s health advisory standard of 300 ppb. All wells also had some amount of iron in one or more tests in the five years studied. Wells 7 and 8 on the north and east sides (respectively) both had iron levels above EPA’s aesthetic standard of 0.3 ppb for all but one of the five years WSJ reviewed.

Where did these contaminants come from? Chlorinated solvents, the graphic explained, come from factories, metal degreasing, and/or dry cleaners and are associated with increased risks of cancer and liver problems. No specific sources were named. As for carbon tetrachloride in Well 3, Seely reported that “numerous test wells” and “months-long study” by the Water Utility of the history of nearby factories, some in operation and some not any longer, “turned up nothing” about the specific source(s).

Manganese, according to the article’s graphic, was “naturally occurring” and iron “occurs naturally or can come from pipes.” Iron and manganese also interact with chlorine added to the water to kill viruses, bacteria, and other microbes, and then they precipitate (settle out) in the pipes, causing discoloration (so the more virus and bacteria problems increase, and the more chlorine added, the worse this problem can get).[5]

While manganese and iron are often from natural sources such as soils and rocks, and therefore frequently found in groundwater, they are also commonly found in landfill leachates, “at concentrations that may be an order of magnitude (or more) greater than concentrations present in natural groundwater systems” (see link). The city (and now county) has found elevated levels of iron and manganese in Truax landfill leachates since it began monitoring in the 1970s (and continues to find elevated levels to date). The WSJ graphic did not mention landfills or other “non-natural” sources of manganese.[6]

Admittedly, finding specific sources of contaminants to Madison’s wells is extremely challenging. Again, as Allegretti wrote in 1990, “Madison’s deep, high-capacity wells draw in water for miles around, making it nearly impossible to identify the source of a particular contaminant.”

But some potential sources, or combinations of sources over large areas, were obvious at that point. By 2006, toxic chemicals (including chlorinated solvents PCE, TCE) from Truax Field (the airport/base, former Truax Landfill and Burke sewage plant), Oscar Mayer, Webcrafters, Hooper Corporation, and many other industries in that area (likely all of them combined) had likely been oozing south and southeast toward Well No. 3 for decades. Well 3 was also very near many old city fill and dumping areas (Demetral, Burr Jones area, etc).[7]

Other old landfills scattered around the city on both the east and west sides could be sources of chlorinated solvents, iron and manganese, and other contaminants to all the Madison wells. These potential sources were not mentioned in the article, even though the city was certainly aware of them. The DNR and city were also tracking a huge chlorinated solvent plume under Madison-Kipp, which they were aware of since the 1990s (and likely earlier).

(In the next year, Mr. Seely obviously learned more about Madison’s leaking landfill problems, and wrote about them in 2007 –see Part III).

“A Loss of Public Trust”

The 2nd part of Seely’s series, “More Money and Action,” focused on the aging water infrastructure in Madison, the increasing number of water main pipes breaks in the city, and the need for more funds to fix these problems.

In the third article, “A Loss of Public Trust,” Seely wrote that the Madison Water Utility “operated largely unnoticed over the years,” but “[i]n the glare of the public spotlight, it became apparent that the Madison Water Utility has problems.”

Manganese was the highly visible water contaminant that raised public ire enough to bring these problems to light. It discolors drinking water, sometimes turning it almost black. Complaints about manganese had been coming in regularly, but prior to early 2005, the utility wasn’t keeping records of these complaints. After the media reported on the manganese issue in early 2006, public complaints skyrocketed, and the utility received as many as 30 complaints a day for a time.

Water Utility employees were told to inform residents who contacted them that this water posed no health risks and running the faucet for a few minutes would take care of the problem. David Denis-Chakroff, Water Utility General Manager, told Seely “[t]hat’s been the message for as long as forever, and it’s the same message you’ll hear in other utilities.”

He sent water utility staffers a memo saying “we must be very careful NOT to imply that the water is unsafe for drinking. If you are responding to a call, you should reiterate to the caller that drinking the water is not a health hazard.”

Denis-Chakroff said this message came from EPA (which was probably true). EPA’s advisory manganese standard of 50 ppb was based on aesthetic considerations (discolored water); the “health advisory” standard for manganese was 300 ppb. At that time, three of Madison’s wells (3, 10, 29) exceeded the EPA aesthetic standard.

But scientific studies available at that time—as is often the case, way ahead of the existing standards–showed that exposures to high enough levels of manganese are connected to neurological problems and are also risky for those with liver problems. West side residents served by Well No. 10 also brought forth peer-reviewed scientific studies “that showed uncertainty about the impact on infants when exposed to high levels of manganese, especially if they were drinking formula already fortified with the mineral.”[8]

One home in the Nakoma area on Madison’s west side, which got its water from Well 10, had levels up to 244,000 ppb in March 2005. This well also served the low-income Allied Drive area.

A manganese task force formed by Mayor Cieslewicz eventually issued a report recommending against drinking or cooking with discolored water. The report should have been done a year earlier, Cieslewicz said. “I think it could have been handled better from the start.”

Well 10 was eventually shut down.

Water Utility “keeps a tight lid on bad news—sometimes to the public’s detriment”

In addition to not keeping records of water quality complaints for some years—a violation of state law–the utility also failed to report other problems, such as a break-in at a water tower, and did not issue a “boil order” to the public as DNR asked, after fecal bacteria were found in water samples on the East Side.

Stunkard was clearly unhappy with the Water Utility’s behavior. “They really didn’t want to publish the notice I wanted them to. But I like to err on the side of public health. I think the problem with the bigger utilities like this is that they are so afraid of negative press. But you can’t fool around with something like fecal bacteria.”

“Administrators with the utility,” Seely wrote, are “entirely dependent on water sales to finance the operation of the water system,” and “bristle at any publicity that reflects badly on the city’s water. As a result they keep a tight lid on bad news—sometimes to the public’s detriment.”

Water Utility leaders defended their decisions, but admitted they made some “public relations” blunders. “I don’t think we made any mistakes,” said Al Larson, the utility’s principal engineer. “But from a public relations perspective, it wasn’t properly handled.”

Water Utility customers told Seely, not surprisingly, that they no longer trusted the utility. One resident, who only saw the problematic manganese results from her home for the first time at a public meeting, said “There is a real erosion of trust. It’s the fact that it seems like they’re trying to hide something.”

Little oversight of the Water Utility

How did this happen? “Utility officials aren’t used to much oversight from city’ officials or the public,” Seely concluded. Mayor Cieslewicz told Seely that one reason for the Common Council and Mayor’s office don’t scrutinize them was “simply because they are not on the tax bill.”

State statutes require the appointment of a Board of Water Commissioners (Water Utility Board) that “manage the utility and oversee its operations,” according to Seely. The Mayor appoints the volunteer board members, who appoint a general manager responsible for operations and supervision of utility staff. The general manager serves at the pleasure of the mayor, who also has the final say on the renewal of the manager’s contract.

Why didn’t the Board catch the growing problems at the Water Utility? Jon Standridge, vice president of the Board at the time, told Seely that utility officials brought “canned presentations” to them, but not substantive issues. “We don’t get enough information,” he said. “For the responsibility we have, we need more details, more information on how decisions are made…The communication needs to be freer, more open and more voluminous. Even though it is not the administration’s intent to cover things up, that has been the perception.”

Cieslewicz opined that more scrutiny by the Board might have helped to avoid the serious problems that occurred in previous years. It might have, for instance, resulted in “a more timely and complete response on manganese…a more forthcoming, transparent approach when dealing with problems such as pollutants and financial issues,” Seely wrote.

“Well from hell”

In the last of his four-part series, “Pollutants Threaten Madison’s Aquifer,” Seely reported that Well 29, the city’s newest well, installed in 2005, was put on standby after less than a year of operation because of high manganese levels.[v] Water Utility officials called it “the well from hell.”

Seely wrote that “the troublesome well is emblematic of the perils facing the utility, from the replacement of aged equipment to pumping clean, reliable sources of water from an aquifer that, though very reliable, is beginning to show early signs of wear from growing urban pressures.”

(With all due respect to Mr. Seely and his excellent reporting, it was a bit misleading to call these “early signs of wear from growing urban pressures.” Allegretti wrote about contaminants reaching Madison’s wells almost 30 years earlier (1978) and then again in 1990.)

The article went on to discuss the need for the Water Utility to create “Wellhead Protection Plans” for all of its 24 wells. “Despite threats to the aquifer, the utility has protection plans for just three of its 24 wells, utility officials said. Without those plans, which the utility says cost about $20,000 each to prepare, the city is limited in how it regulates potential polluters near municipal wells. As the city develops, these wellhead protection plans are becoming more important.”

Tom Stunkard from DNR, who oversaw regulation of the Madison Water Utility at that time, said wellhead protection plans would help the city protect its wells and its aquifer. “It seems like a planning tool Madison is missing out on.”

Unfortunately, many of Madison’s wells were already contaminated by that point—too late for a “planning tool” to fix the problems. Still, it is good that the Water Utility took steps to create wellhead protection plans for all of its wells in subsequent years (though their effectiveness is doubtful—see later stories).

“What we do now may come back to haunt us in years or in decades.”

Seely’s “Pollutants Threaten Madison’s Aquifer” repeated one of Madison leaders’ infamous, disingenuous assurances–one that community activists have heard many times over: “Madison is blessed with a vast, deep aquifer that’s shielded from contaminants by a layer of shale, hydrogeologists say.”

But hydrogeologists and Water Utility officials knew this was only partially true, and the finding of multiple contaminants in many of Madison’s wells clearly show that. In some areas of the city—such as Truax Field, with the ancient pre-glacial river valley beneath it—there is no shale.

Further, scientists were well aware by this time that even the in the areas with Eau Claire shale beneath them, the shale has cracks or “fractures” that allow contaminants through from the upper to the lower aquifer—sometimes extremely quickly.

Nevertheless, city officials and scientists continued to make this assurance, and continue to do so to this day.

Bradbury also pointed to a hydrogeological reality that Allegretti’s articles had raised almost 30 years prior: Because of our heavy municipal well pumping, we are now drinking the lakes.

“Dane County residents are even changing the water cycle here” said Ken Bradbury from WGNHS. “Studies have shown the water level in the aquifer has dropped nearly 60 feet from historic, predevelopment levels,” he said. “It used to be that the Madison lakes were replenished by groundwater. Now that cycle has been reversed with municipal wells near the lakes deriving significant quantities of water—roughly 25 percent of the water they draw—from downward leakage from the lakes themselves.” (highlights added)

“This phenomenon, Bradbury said, means basically that the pollutants we put in the lakes, such as pesticides, are likely to also eventually show up in our drinking water. “What we do now,” Bradbury said, “may come back to haunt us in years or in decades.”

“How we choose to live can have a significant effect on the quality of the water we drink,” Seely added. “Even when pollutants from factories and other sources in the city of Madison have to leach through layers of soil and stone, they eventually reach the aquifer.”

“One of the most important things,” Bradbury went on, “…is that the groundwater used in Dane County originates within the political boundaries of the county.” Seely translated–“meaning, it’s our own pollutants we have to worry about.”

What happened to Well 3, Well 29, and other contaminated wells? What did the Water Utility do to attempt improving public trust? Continued in Part III…

[1] DNR’s Stephen Ales March 7, 2022 comments to the Air National Guard says: “DNR is supportive of evaluating the hydraulic connection between the unconsolidated aquifer and the bedrock aquifer. This is especially important given the bedrock valley shown on Figure 10-5, the ability of high-capacity bedrock wells to induce downward gradients, and the presence of municipal wells and private wells that draw water from the bedrock and are shown to have PFAS compounds in them.”

[2] On First Street just off E. Washington—the future site of Madison’s public market. This well was built on the site of the city’s first sewage treatment plant, built sometime around 1899-2001 (but proved to be dysfunctional within a few years and was abandoned before the Burke sewage plant was built near Oscar Mayer).

[3] Who knows how long East High students and other east side Madison residents drank this water contaminated with carbon tetrachloride? It was very likely much longer than “a short time.” By 2006, toxic chemicals from Truax Field, the former Truax Landfill and Burke sewage plant, Oscar Mayer, Webcrafters, and many other industries (likely all of them combined) had been oozing south and southeast down the ancient pre-glacial river valley toward this well for decades. The well was also very near many old city fill and dumping areas.

[4] Residents couldn’t taste or smell carbon tetrachloride, but started asking questions when their drinking water started turning black from manganese.

[5] Chlorine is sometimes added to water purposely to pull out the iron and/or manganese—e.g., https://www.jstor.org/stable/23349403 and https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40899-015-0017-4.

[6] According to EPA, manganese is also “commercially available in combination with other elements and minerals; used in steel production, fertilizer, batteries and fireworks; drinking water and wastewater treatment chemical.”

[7] Some of Oscar Mayer’s wells were already contaminated with PCE and TCE by the 1980s, and all of them were shut down by the early 2000s.

[8] Though regulated as only an “aesthetic” contaminant to date, numerous scientific studies indicate that at high enough levels, manganese can cause serious neurological effects. On Feb. 4, 2015, Manganese was listed on the EPA Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) fourth Contaminant Candidate List (CCL 4). Nominators for the CCL 4 (typically toxicologists and other scientists), “cited more than 20 recent studies that indicate concern for neurological effects in children and infants exposed to excess manganese, which were not available at the time manganese was considered for the first Regulatory Determination or CCL 3 (in 2009). In addition, new monitoring studies from USGS and drinking water monitoring information from several States supported an earlier survey (i.e., the National Inorganics and Radionuclides Survey), which indicated manganese is known to occur in drinking water. EPA eventually determined that the new health effects information and additional occurrence data merit listing manganese on the CCL 4 in December 2016.