PFAS hits in Madison drinking water wells

By Steven Verburg, for the Isthmus

In a Jan. 16 guest column in Isthmus, a Madison city water utility spokesperson took a page from President Trump’s playbook by falsely accusing journalists of dishonesty.

The column by Amy Barrilleaux was a reaction to an Isthmus cover story raising critical questions about official assurances that Madison drinking water is certainly safe.

Reporter Kori Feener interviewed national experts about important scientific research that local leaders have disregarded.

Feener’s article quoted scientists from Harvard, Brown and Boston universities, and a toxicologist who retired in October as director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program.

The experts said the best available science doesn’t support the certainty expressed by local officials that levels of certain contaminants aren’t high enough to make drinking water dangerous.

At issue is a huge family of hazardous compounds manufactured for use in consumer products and firefighting foam. The synthetic substances are called “forever chemicals” because they are so persistent in the environment.

The umbrella acronym for these compounds is PFAS. They are linked to serious health problems including kidney cancer, liver dysfunction, reproductive problems, high cholesterol, weight gain and weakened immune response.

Before I retired as a daily newspaper reporter in June, I wrote extensively about the reluctance of federal, state and local governments to undertake environmental assessments that could lead to costly PFAS cleanups, and official adherence to health advisories that have been widely criticized as understating risks.

Feener’s article drew into sharp focus the differences between the views of Madison officials and national experts.

In contrast, Barrilleaux’s column described only the city’s view. And in a classic act of Trumpian projection, Barrilleaux cried out for context: “I know not every detail can make it into a story. This is an incredibly complex topic. But I do expect journalists to include basic details that offer context for people in Madison.”

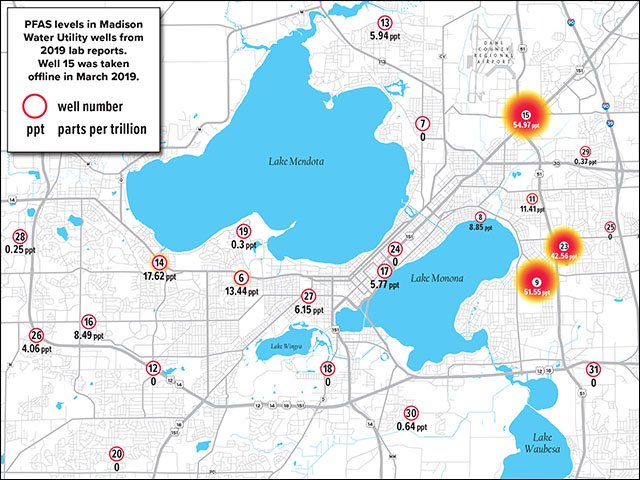

Madison and Dane County officials have embraced a disputed federal advisory of 70 parts per trillion as a safe level for two types of PFAS combined — PFOA and PFOS. Last year the state proposed a 20 parts per trillion standard, and local officials also cited it. Levels in Madison drinking water for those two types of PFAS don’t exceed the proposed state limit.

But the experts quoted by Feener pointed to research trends that may mean that with PFAS, like lead, no amount is safe.

Meanwhile, the federal advisory and state proposal cover only two of the thousands of types of PFAS. Many others have been found in Madison water.

If you read Barrilleaux’s piece only, you’d think it was a novel and foolish idea to judge health risks by adding together the level of each and every kind of PFAS found in a given water sample.

Feener’s story includes Barrilleaux’s assertion, but adds the words of a leading toxicologist who isn’t so sure: “We don’t know whether PFAS are acting additively or synergistically…. As a first cut, just adding things up to get an idea of how much is around, I don’t think is a bad approach.”

Barrilleaux doesn’t confront the experts’ science. Instead she attacks journalists, claiming suppression of crucial information.

Barrilleaux’s assertion of a cover up? Too little has been written about her agency’s voluntary 2017 switch away from an inadequate federal testing method for PFAS.

“I’ve given this information to several reporters covering this issue, but it’s never made it to print until now,” Barrilleaux wrote. “I understand. It doesn’t fit the narrative of a city waiting for others to act, of a city that’s not paying attention to the science on PFAS.”

Not true. There’s been no conspiracy of silence.

Starting with the first PFAS article I wrote in December 2018, I reported on the change at least four times.

But this is 2020. It’s a bit much to claim you are being persecuted because a good move you made three years ago isn’t making the news anymore.

Similarly bogus is Barrilleaux’s objection to “the narrative of a city waiting for others to act.”

Many water utility actions on PFAS have been reported. They were often prompted by public demands.

But it’s just a fact that local leaders have been waiting. Specifically, they have been waiting for a cleanup to be initiated by a military unit that says it can’t afford it.

In 2018 and 2019, the city and Dane County agreed to wait for the Air National Guard 115th Fighter Wing to initiate cleanups of hotspots around Truax Field, where all three bear responsibility for PFAS spills. No cleanup has taken place.

In December, the county stepped forward with a plan to wait some more. The county’s environmental consultant questioned the need for a cleanup of the hotspots and reported plans to take preliminary steps before deciding whether or not to begin the soil and water testing needed to plan a cleanup.

The consultant acknowledged county airport stormwater was sending PFAS into public waters, but argued installing filters in stormwater pipes as an interim measure was “impractical and infeasible.”

A cleanup will be expensive. A costly cleanup could complicate efforts by local leaders to bring F-35 jets to Truax. But the longer these highly mobile contaminants stay in water, the farther they will spread and the more it will cost. Recently, there’s been new confirmation of contaminated fish in Lake Monona and Starkweather Creek.

At a time when news organizations are struggling economically, and killing messengers has been taken to dangerous extremes nationally, it’s galling to see local resources spent making unfounded attacks on journalists.

Maybe Madison leaders see how well the politics of distraction are working in Washington. Undermining an independent press is sure cheaper than cleaning up the water.

Steven Verburg is a former reporter for the Wisconsin State Journal. This is a slightly expanded version of his guest column that appeared in print.